Design Research

Revolutionizing Education: The Power of Systems Thinking in EdTech

Systems thinking is a powerful approach to understanding and addressing complex problems in education technology.

AUTHORED BY:

Sheryl Cababa

As a parent, I have firsthand experience with how the pandemic has affected students and their education. My elementary school-age daughter recently took a standardized test, and you could see that her progress, across subjects, fell dramatically during the time that she had to attend virtual school in 2020. Her progress has since improved significantly, but it speaks to lost time and learning.

She is not alone. In national test results released in the United States in September 2022, the National Assessment of Educational Progress tests showed that “9-year-olds lost ground in math, and scores in reading fell by the largest margin in more than 30 years.” Not only that but even more alarming from an equity standpoint, some students were affected more than others: “In math, Black students lost 13 points, compared with five points among white students, widening the gap between the two groups. Research has documented the profound effect school closures had on low-income students and on Black and Hispanic students.” The reasons these students were hit hardest include those longer school closures, as well as ongoing lack of consistent internet access, fewer resources for those school environments, and a host of other systemic issues.

This is just one example of how broad context, and a myriad of varied challenges, can create a complex set of problems that can be difficult to solve with singular solutions. In the tech industry, we often take a user-centered design approach, thinking that that’s all we need to understand in order to solve problems with things like software. We focus on the user alone, aiming to gain an understanding of the individuals who use a product or service: their context, needs, and challenges.

Yet with complex problems like those in education, the user is just one part of a larger ecosystem of stakeholders—a single player in a series of causal and correlating events. For designers, the first step is to reach beyond user-centered design and approach systemic problems with systems thinking.

Systems thinking is a holistic approach to problem-solving that emphasizes the interconnectedness of various parts of a system. In the field of education technology (EdTech), this approach can be used to design and improve educational systems, tools, and resources that support student learning and development. By considering the complex relationships and interactions between various components of an educational system, EdTech developers can create solutions that have a greater chance of having an impact.

So why is it important to understand problems and context more broadly? Why can’t designers just solve the problems right in front of them? This narrowly focused approach can lead to new problems, and worse, because of the scale at which many EdTech products operate, negative societal impact and unintended consequences. Those who work in education know that EdTech products are not a silver bullet. Knowing that many design decisions happen within a larger system of context helps designers not only make better choices but also activate a combination of their design skills and systemic understanding to align and facilitate many stakeholders—not just EdTech designers and developers— to drive change.

EdTech is only one piece of the puzzle

Take this example from research conducted by University of California researcher Matthew Rafalow. He studied three different school environments, all of which had fairly equivalent access to technology, but with huge differences in student demographics. The first school was an affluent school with predominantly wealthy white students. The second school had students who were mostly middle class and Asian, about 10% of whom received free or reduced lunch. The third school was working-class Latine, with 87% eligible for free or reduced lunch.

Though all three schools had similar access to technology, as well as students who were adept and experienced with interacting with different forms of digital technology, there was a difference in how they were treated by teachers. While in the wealthy white school, playing with and experimenting with digital technology was considered a creative outlet and learning opportunity, the middle-class school and working-class school educators tended to hold the perception that the students’ use of technology was either a nuisance (students ‘hacking’ into the systems) or irrelevant (“it won’t be something they need in the future”.)

Of course, this has nothing to do with the technology in front of students and their ability to use and interact with it, it has more to do with the mental models, and unconscious biases, of the people who surround them. It’s a good example of how technology isn’t just about access, it’s about understanding the context in which it sits, the mental model that stakeholders have, and how it affects different students in the system. A systems thinking lens helps to uncover these potential challenges.

A practical framework for getting started with systems thinking

You may be a designer, an EdTech developer, an educator, or a funder trying to figure out how to have the most meaningful impact. Knowing that making decisions in education takes a village, it’s a good idea to start with alignment with other stakeholders from a systems-thinking perspective.

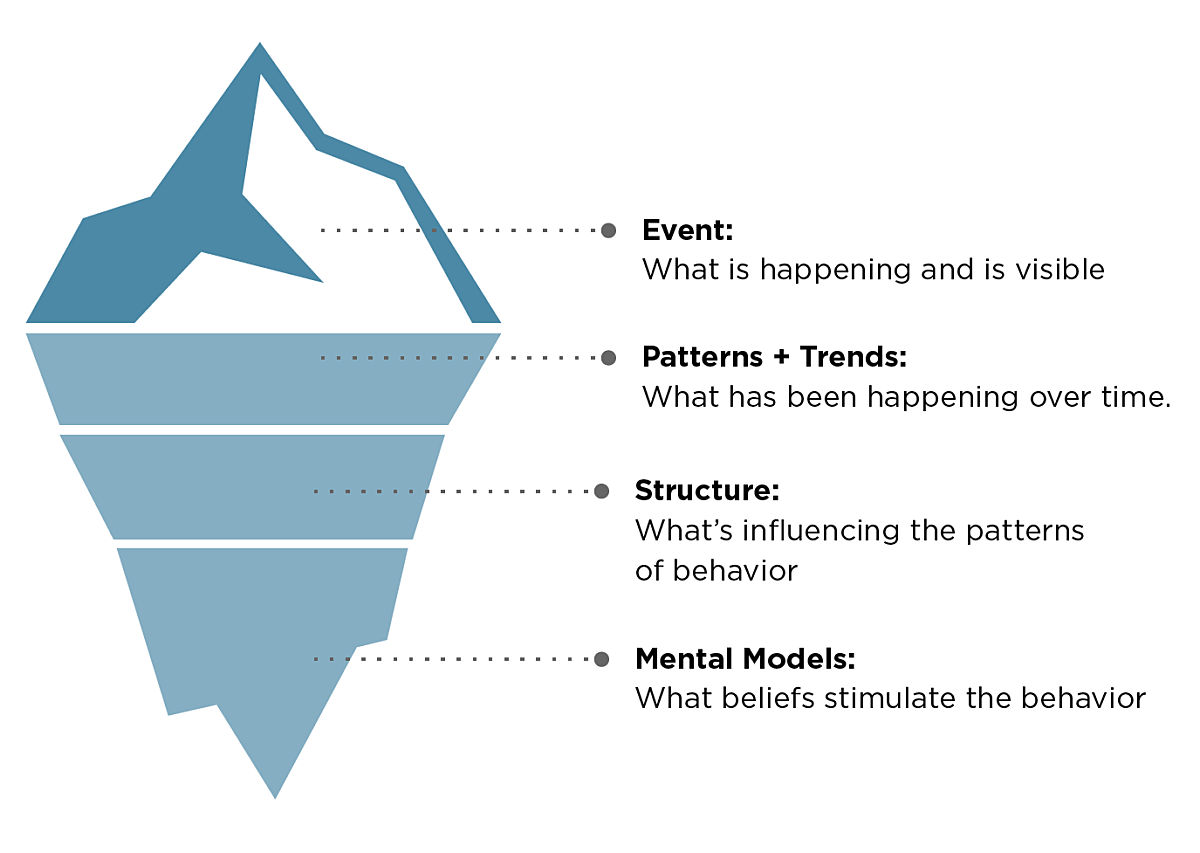

A simple way to get started is by mapping your existing system. There are multiple ways of doing this: stakeholder mapping, causal loop diagramming, and other frameworks. One easy framework is the iceberg model. The idea is that you take a visible issue that you and your stakeholders are trying to solve, and unpack what lies under the surface (hence, the iceberg metaphor). The model has four different layers, representing patterns just below the surface, going all the way to mental models that affect every layer above it.

With a multidisciplinary group of stakeholders who can represent knowledge and expertise for various parts of the system, you can workshop the iceberg model layer by layer to develop a shared understanding of the problem space. In solving problems for education, these stakeholders could be everyone from education policymakers, school district administrators, and technology developers, to researchers and funders. Coming together is an important aspect of systems thinking, and combined with design thinking’s visual sensemaking and facilitation, is a powerful way of unpacking problems.

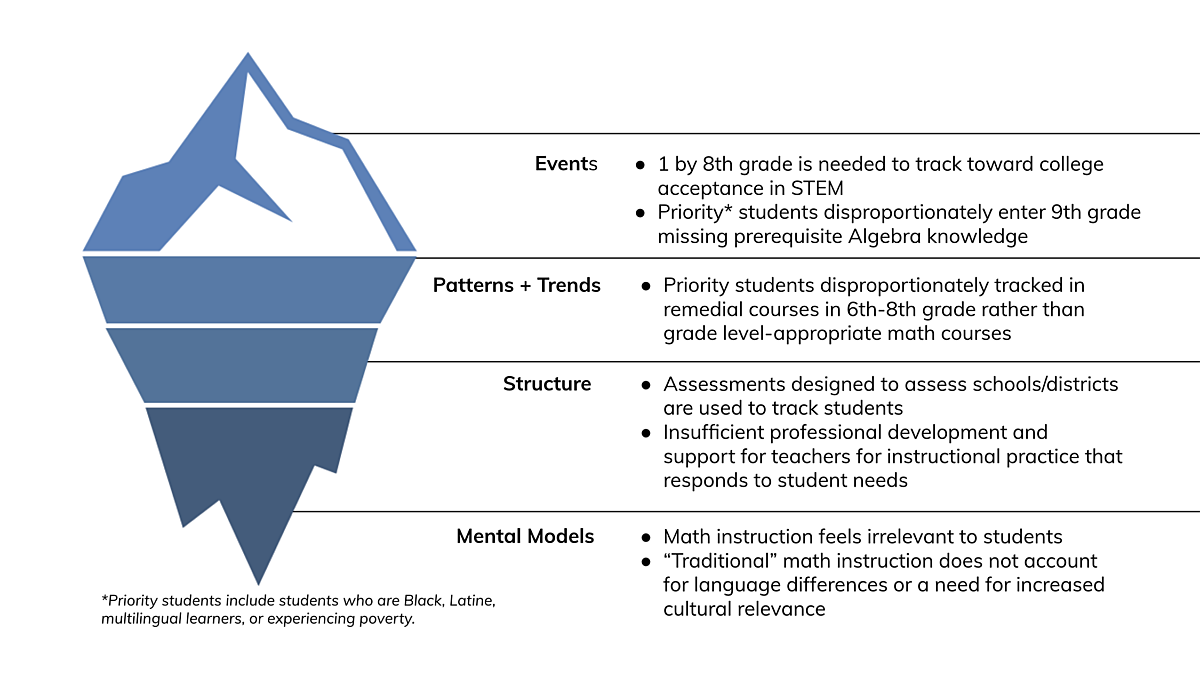

An example of the iceberg model in action is a capture of how we thought about the impact of Algebra 1 on racially marginalized students. (You can see the outputs of this work in our Balance the Equation project.) Black and Latine students, and students from low-income backgrounds often lack support from their schools to help them excel in math, and Algebra 1 in particular plays a crucial role in college preparedness. Throughout this project, we worked extensively with experts in equity and mathematics, bringing together diverse stakeholders to workshop both an understanding of the existing system and working to envision potential areas of intervention. You can see how a high-level understanding of the problem space for a topic like this can be synthesized using the iceberg model.

Though this iceberg model may feel fairly high-level and does not speak to solutions yet, it creates a starting point for understanding where stakeholders can possibly intervene. This leads to creative thinking about possible solutions: they can fall into the categories of technology, pedagogy, policy, and even activism. And again, it sets the stage for a shared understanding that no singular solution is a silver bullet, but change can be made in many different places in the system.

A powerful tool

Systems thinking is a powerful approach to understanding and addressing complex problems in education technology. By considering the interrelated components of an educational system and the relationships between them, edTech developers can design more innovative solutions that support student learning and development. Applying systems thinking to edTech also allows us to think beyond individual components, like a particular app or software, and instead focus on the entire system and its impact on education as a whole. Embracing this holistic perspective can lead to more comprehensive and sustainable change in education. It is important to note that systems thinking is a continuous process and not just a one-time solution. It is essential to keep evaluating the system and make necessary adjustments and improvements along the way to achieve the strongest impact for all learners.

At Optimistic Design, as individual designers, we arrived at the organization with our own versions of Equity-Centered Design mindsets, processes, and tools. We continue to learn and develop the practice within our organization. Many of our approaches are heavily influenced by our individual, lived experiences as designers with intersecting marginalized identities as well as racial and social justice movements, abolition, systems thinking, social work, disability activism, etc. We look to practitioners like Antionette Carroll, Liz Jackson, and Sasha Constanza-Chock who continue to integrate traditional design education and practices. We have valued and learned from the work of Design Justice Network and the Equity Design Collaborative.

Want to learn more about our Equity-Centered Design work? Contact us.

Let’s Design the Future of Learning, Together